-

-

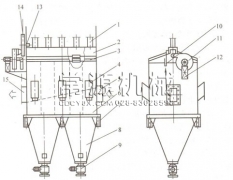

脉冲布袋除尘器

脉冲布袋除尘器基于袋式除尘器进一步完善,具有除尘净化效率高、处理能力大、性能稳定、操作方便、滤袋寿命长、维修工作量小等优点,广泛用于冶金、建材、水泥、机械、化工、电力、轻工行业的含尘气体的净化与物料的回收,以确保环保达标排放!

在线咨询 139 8202 0315 -

-

高速分散机

分散机是搅拌机的一种,采用高速搅拌器(如圆盘锯齿型搅拌器)可以在局部形成很强的紊流,通常对物料有很强的分散乳化效果,所以对这类高速搅拌机又称为高速分散机。适用于涂料、染料、油墨、造纸、胶粘剂等化工行业对液固相物料进行搅拌、溶解和分散。

在线咨询 139 8202 0315 -

-

三辊研磨机

三辊研磨机简称三辊机,通过水平的三根辊筒的表面相互挤压及不同速度的摩擦而达到研磨效果。 三辊研磨机是高粘度物料最有效的研磨、分散设备,主要用于各种油漆、油墨、颜料、塑料、化妆品、肥皂、陶瓷、橡胶等液体浆料及膏状物料的研磨。

在线咨询 139 8202 0315 -

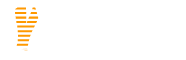

螺旋输送机

螺旋输送机也称蛟龙螺旋机。它能水平、倾斜或垂直输送,具有结构简单、横截面积小、密封性好、操作方便、维修容易、便于封闭运输等优点。适用于水泥、粉煤灰、石灰、粮等无粘性的干粉物料和小颗粒物料。

1398 2020 315

-

敞口包装机自流式

敞口包装机主要应用在医药、化工、农药、非金属、涂料、陶瓷等行业的定量包装。如:陶瓷粉、碳酸钙、可湿粉、碳黑、橡胶粉、食品添加剂、颜料、染料、氧化锌、医药粉等。

在线咨询 139 8202 0315 -

机械设备生产销售流程非标设备设计、制造、销售

1985

始于

10,000,000

注册资金

1500

用户数以上

6000

交付产品以上

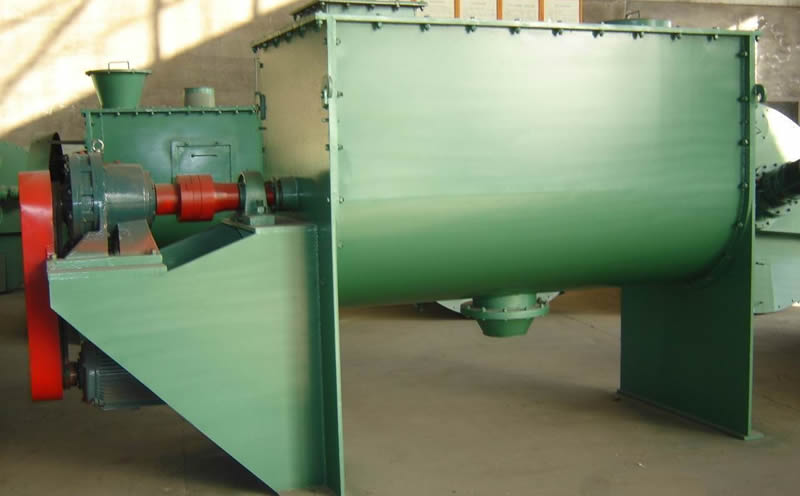

干粉砂浆设备

干粉砂浆设备生产线主要是由提升机、预混仓、小料仓、混合机、成品仓、包装机、除尘器、电控柜、气相平衡系统组成

保温砂浆设备

保温砂浆设备生产线主要是由提升机、预混仓、小料仓、混合机、成品仓、包装机、除尘器、电控柜、气相平衡系统组成

腻子生产设备

腻子粉生产设备在螺带干粉混合机基础上增加电动上料机、储料罐、自动灌装机及电控柜构成高效合理,操控便捷流水作业体系

油漆涂料设备

涂料油漆设备系乳化分散罐、调漆罐、管线式乳化机、卧式砂磨机、粉体加料罐、混合机、计量包装设备等组成的油漆涂料生产线

聚羧酸减水剂

聚羧酸常温合成设备由反应搅拌系统,小料加投系统,计量称重系统,电控安全系统组成,操作简单,占地面积小成本低!

树脂生产设备

树脂生产设备由树脂反应釜、填料柱、竖式冷凝器、不锈钢冷凝器、分水器等作为树脂生产的主体设备,适于生产各种树脂等

化工生产设备

化工生产设备主要是指部件是静止的机械,诸如冷凝器、分离设备,容器、搅拌罐、反应釜设备等,有时也称为非标准设备

粉尘治理设备

粉尘处理设备用于治理家具厂、木板厂、矿山粉尘、陶瓷粉尘、医药粉尘、纺织粉尘、抛丸机粉尘等

真石漆设备

真石漆设备用于生产陶磁石,陶砂骨材,多彩花岗石漆单彩石材,调和多彩石材,天然真石漆多彩仿石漆仿花岗岩大理石涂料

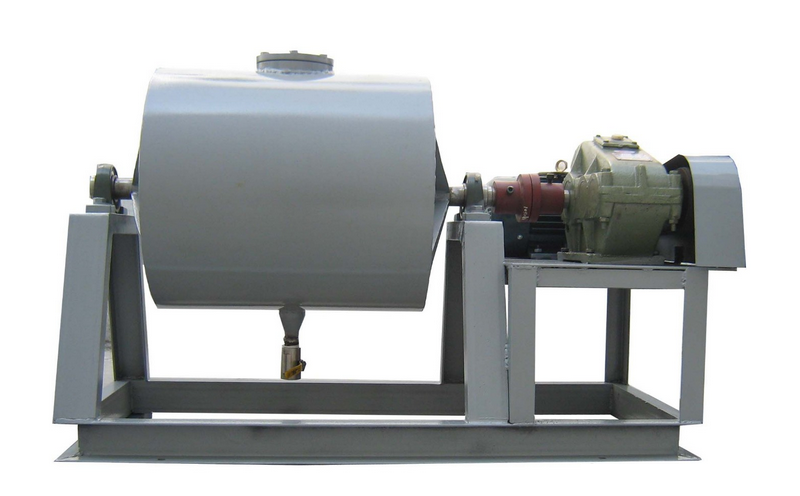

成都常源机械设备有限公司

我们的优势

成都常源机械设备有限公司源于1985年成立的仁寿县常信源机械厂,注册资本1000万元,是国内从事化工、医药设备、食品设备、涂料油漆设备、粉体设备、环保设备生产的企业。 集粉体混合、搅拌、传输、计量、包装,流体搅拌、分散、研磨、提取、回收、干燥、密闭反应的综合机械制造企业,产品在石油、化工、建材、矿山、医药、食品等行业的应用非常广泛。 工厂技术力量雄厚,基础设施齐备,并在高校设有粉、流体实验室。工厂拥有各类专业技术人员,其中焊接技工20人;高工1人;工程师4人。工厂拥有多台手弧焊机、埋弧焊机、氩弧焊机、卷板机、数控切割机、试压泵及车床、钻床、刨床、铣床、锯床,成套除尘器骨架生产器械等。 工厂建立了健全的质量管理体系,产品质量始终稳定可靠,深受用户欢迎。 欢迎新老客户莅临公司指导工作!

生产制造经验丰富

核心成员近30年的机械制造经验,专业技术员工队伍稳定,平均在厂工龄10年以上,确保可靠的产品质量和效率。

生产质量层层把关

具有健全的质量管理体系,从原材料进厂到产品出厂的各道工序均进行了严密的质量控制,产品质量始终稳定可靠。

本地源头制造厂家

各种非标机械设备就在本地生产制造,直接面向最终用户,沟通高效,没有中间商赚差价,既确保质量又降低成本。

荣誉资质

Copyright © 成都常源机械设备有限公司. 蜀ICP备09023542号-5蜀ICP备09023542号-8